War of Attrition, 1969-1970

By Tom Cooper

Sep 24, 2003, 20:09

[/b][/b]

[b][b]

After the end of the Six Day War, the Israelis attempted to develop good defensive positions along the borders of the newly conquered Sinai Peninsula and on Golan. The Arabs - especially Egypt - were still under the shock of the severe defeat, but wanted to hit back at every opportunity. Initially, the Egyptian Air Force, re-named back from UARAF in 1968 - was foremost trying to shake-down the sad memories and also the wrong lessons from its Soviet instructors, who trained the Arab pilots to fight at high levels and intercept straight-flying targets using MiG-21s and air-to-air missiles. Neither the aircraft nor ist main armament, the R-3S (AA-2 Atoll) missile, were actually built to fight at low levels and against hard manoeuvring opponents, but the Egyptians were now about to adapt them for this task. Namely, the Israelis have deployed several long-range radar stations on mountain peaks of Sinai, as well as a number of MIM-23 HAWK SAM-sites, while IDF/AF interceptors were permanently based at several local airfields, foremost Bir al-Jifjafa (now renamed into Refidim), from where they were able to swiftly react to every Egyptian attack.

Recognizing the Israeli superiority in air combat arena, but willing to hit back, the Egyptians properly concluded that in order to hit their targets in Sinai and return safely, they had to use the moment of surprise. Consequently, their fighter-bombers had to fly low. Another consequence was that the Egyptian interceptor-pilots had to learn how to fight with their MiG-21s at low levels as well, then this was where they were now about to engage the Israelis. While they would be learning to do so, and because there was no guarantee that the MiGs could always intercept their targets in time, the SAMs were to increasingly take over the air defence of most important areas.

The Israelis, on the other side, were foremost interested in holding the Egyptians back, but only enough not to provoke a major confrontation. From their standpoint it was imperative to impose heavy attrition upon the Arabs, showing them that all their efforts were in vain.

Despite the losses they were about to suffer, the Egyptians would not give up: they would neither stop learning nor attacking the Israelis. Consequently, this process resulted in very intensive operations over the Suez and the Sinai, flown by both sides. It was eventually to become so painful and costly for both sides, that by 1970 this “War of Attrition” was more than either Israel or Egypt could bear. Both sides were therefore more than glad to be able to disengage under the pressure of foreign powers, the USA and USSR.

UARAF back to EAF

The Soviets were relatively swift to replace the losses suffered by the UARAF during the Six Day War: by the end of the year over 70 MiG-21PFs and MiG-21PFMs were delivered, together with a similar number of MiG-17Fs, and some Su-7s. Consequently, the UARAF did not took long to rebuilt its strength - at least theoretically – to the levels from before the war in 1967. However, the UARAF has suffered a heavy loss in qualified pilots and needed not only several years to train new crews, but even more so, working according the “trial-and-error” method, it needed time and combat experience to train these properly, while fighting from a position of a humiliating defeat.

Besides, the Egyptians had to go through this process with the same equipment they had before and that was not only defeated in the Six Day War, but also more than well-known to the Israelis. The Soviets, interested in Egypt only from the aspect of the Cold War struggle for influence in the Middle East and Africa, were neither ready nor really able to deliver aircraft and armament equal or superior to that of the Israelis. At the time, the advanced versions of the MiG-21PF, and the old R-3S missile, were actually the best they could supply. Certainly, they had a number of slightly more powerful and capable systems in service at home, but they would not supply these to the Arabs, and the worth of such fighters like Yak-25 or Su-9 for a conflict like fought between Egypt and Israel can only be questioned. The USSR, namely, was only now developing a new generation of fighters – including MiG-23 and MiG-25, as well as the Su-15 - that were designed to challenge such Western types like F-104 Starfighter, F-105 Thunderchief, and the F-4 Phantom in power and armament, and these were not to become ready for service for a number of years to come.

Therefore, the Egyptian Air Force – renamed back from “UARAF” in 1968 - entered what later became known as the „War of Attrition“ not only undermanned, but also undergunned and undertrained.

The Syrian Arab Air Force (SyAAF) was to become the “third” factor in the air-to-air arena of the War of Attrition, but – even if it was not to see anything like an involvement of the Egyptian or the Israeli air forces – it was one to go through the most dramatic development in the time between 1967 and 1973. From a relatively small force, capable only of limited point defence and badly damaged by Israeli raids in June 1967, the SyAAF was developed into a strong and professional force. The MiG-21-force was significantly increased, and the MiG-17-units reinforced. The Syrians have also got Su-7s, but in general their fighter-bombers did not take part in the fighting before the next war in 1973.

In all possible publications about the Egyptian and Syrian air forces it is often explained how both were reorganized along “Soviet principles” after the Six Day War. This was only partially truth. For example, while both the EAF and the SyAAF have had their squadrons put under command by air brigades or air regiments, the importance of the squadron remained the same as before – something that was unheard of in the Soviet system. The Egyptians had their Air Brigades organized already before the war in 1967, and have subsequently only changed their designations: this was done several times, but was essentially everything. Actually all the Egyptian and Syrian units very much continued following their traditions, even if many – especially in the EAF – were re-named, or split into two units, re-equipped with different aircraft, while some were disbanded. Even the use of unit insignia was not discontinued: it was only so that none was applied on aircraft. Within the SyAAF there was even less of the change, then the Air Brigade structure was not introduced until after the war in 1973, even if the number of units was doubled between 1967 and 1973.

Other Arab air arms were not to take part in the War of Attrition, even if an Algerian detachment was active with the EAF until 1968, and from 1970 again (albeit it was stationed in Libya during its second stint).

Above and bellow: immediately after the Six Day War the Egyptians started camouflaging their MiGs - a late measure, proposed several times already before the catastrophe of the 5 June 1967. In emergency, and lacking other suitable colours, the Egyptians used a stock from a car factory at Hulwan! This early camouflage pattern was later to become known - albeit in a modified form - as "Nile Valley". It consisted of Sand, Black, and Light Grey colours. Serials were still applied, albeit not as prominently as before, and unit insignia completely disappeared: after all, innitially after the Six Day War all the surviving aircraft and pilots were concentrated within two "Big Squadrons", and only slowly through 1968 were the old units re-established. (all artworks by Tom Cooper unless otherwise stated)

New Friends for the IDF/AF

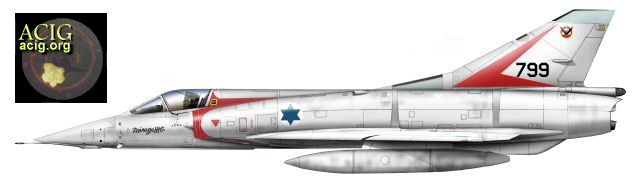

The IDF/AF has suffered some pretty painful losses in aircraft and pilots during the Six Day War, and was then hit severely by the French embargo on arms deliveries, introduced because the French President de Gaulle felt personally insulted by the Israelis initiating the war despite his warnings not to do so. While they were later able to recover or clandestinely receive some of the equipment ordered from France, the IDF/AF was not reinforced by the acquisition of 50 Dassault Mirage 5s, built specifically to Israeli specifications. Also, the cooperation between the emerging Israeli defence sector and such French companies like Dassault and SNECMA was interrupted, and the development of what later became known as Israeli Aircraft Industries almost stopped, interrupting also the intention all the surviving Mirage IIICJs to be re-engined with the much more reliable SNECMA Atar 9C engines, but also some other projects.

This was soon to change, however, as in the following years Israel was to establish excellent relations with the USA, that resulted in important reinforcements for the IDF/AF. By 1967, namely, the USA became deeply involved in the Vietnam War, where the US Air Force and the USN fliers were encountering an enemy increasingly equipped with sophisticated fighters and SAMs of Soviet origin. Given that the Israelis have captured immense amounts of weapons and spare parts on Egyptian airfields on Sinai during the Six Day War, and that these were highly interesting for the USA, there was now a good reason for direct cooperation between Jerusalem and Washington, which was to become obvious once the US-built fighters started arriving in Israel.

Israel has actually placed the first direct order for new combat aircraft in the USA already before the Six Day War, when it first showed interest in the Grumman A-6 Intruder, but finally ordered 48 Douglas A-4 Skyhawks instead. But, this order was postponed due to the war. In 1968, eventually, the USA started supplying Skyhawks to the IDF/AF. On the other side, impressed by the performance of the McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom in Vietnam, the IDF/AF showed interest in acquiring this type as replacement for unreliable Vautours. Israel was not a rich country at the time, and could not afford large amounts of expensive US fighters. However, it could furnish the USA with immense amounts of remarkable intelligence, some of which the US military could badly need for fighting what it was actually designed for: the main war against the USSR. This was something worth more than any money could pay.

Namely, before, during and after the Six Day War the Israelis have captured considerable amounts of Soviet-built equipment. Complete equipment of several SA-2B Mod 1 SAM-batteries and a number of V-75 missiles was captured, together with associated Fan Song radars. At least as important was the fact that the Israelis have had an intact MiG-21F-13 in their hands, flown in by a defecting Iraqi pilot, in 1966, but also that they have captured either three or six Algerian MiG-21F-13s, when these landed at el-Arish AB, on 6 June 1967, after a mistake within the Egyptian High Command caused them to be sent to an airfield that was meanwhile captured by the Israelis. One of the Algerian pilots that realized the situation fired at his MiG, damaging it badly (and was in return shot and injured by the Israelis), but the other aircraft were taken intact. The damaged MiG was subsequently repaired with the help of large amounts of spare parts found in the depots of Egyptian airfields. These were sufficient to keep also the ex-Iraqi MiG-21F-13 (the well-known “007”) operational, but then proved sufficient for the IDF/AF to put together an operational MiG-17F! According to some unconfirmed reports these aircraft might have been pressed into service within a unit that became known as a “Soviet Squadron”, and which in 1968 was further reinforced. Namely, in that year two Syrian MiG-17-pilots landed in Israel due to a navigational mistake: while their pilots were returned to Syria, both MiGs were impounded in Israel. Sometimes later the Israelis also captured an Egyptian Sukhoi Su-7 that made a soft landing on a sand dune in Sinai, after being damaged in combat with IDF/AF Mirages.

Finally, during the Six Day War the Israelis have captured also R-3S missiles on Egyptian airfields. According to US reports, a total of 238 such weapons was taken; some Israeli sources deny this, stressing that only between 40 and 80 were found. Whatever the truth, the fact is that at least a dozen were later sent to the USA, around two dozens fired in testing in Israel, while some were finally pressed into service with the IDF/AF. Namely, the “indigenous” Israeli Shafrir Mk.1 air-to-air missile proved a failure, and after the Six Day War the IDF/AF found itself without any useful weapon of this type: the Shafrir Mk.2 was still in development, while the US-built AIM-9 Sidewinder was not yet available. Consequently, the Israelis have armed a number of their Mirage IIICJs with the R-3S, and – according to USAF records – started using the weapon in combat (conflicting Israeli reports indicate that some kills were scored by the weapons, but others say that while deployed, they were eventually never used in combat).

Clearly, having all of these assets at hand was making the Israelis exceptionally interesting for the USA. The situation was only to improve – from the Israeli standpoint – in the following years, when the IDF/AF started encountering Soviet-built systems in Arab arsenal that were far superior to anything the USA have encountered in Vietnam. Eventually, the direct US involvement on the Israeli side, and the corresponding intensification of the Soviet involvement on the Arab side, were to have some quite unpredictable repercussions – not only on the political arena, but even more so in the arena of air warfare.

Basic Principles

Interestingly, despite their ferocity, the air combats during the War of Attrition have not influenced the development of new weapons in the way this was the case with the air warfare during the subsequent war in 1973. This even if most of the clashes between the Israelis and Egyptians have not only confirmed classic theories about the methods of fighting for air superiority, but have also seen the introduction of many new weapons. All of these weapons – with exception of electronic countermeasures – however, were already existing and developed before the outbreak of the Attrition War. Besides, neither side was actually fighting for some kind of a clear air superiority in strategic sense: the Israelis could not establish air superiority over Egypt, for example, without starting an all-out war, while the Egyptians could not establish air superiority even over Sinai, because they lacked corresponding weapons system and personnel needed to make them capable of this task. Instead, both sides were doing their best to simply cause losses to the other side.

Consequently, there was no frontal collision between the EAF and the IDF/AF, but rather a series of piecemeal campaigns, limited in scope and intention, all the time followed by periods of relative peace, used for re-assessments of the situation, acquisition of new equipment (if available), additional training and planning of new operations. The air-to-air battles were characterized by high tempo and swift manoeuvres, in which each side attempted to inflict as much damage to the other as possible within the shortest period of time and at lowest possible cost. Neither side possessed the distinct initiative, even if - due to distinctive advantages in training and technology - the IDF/AF was usually able to operate according to own ideas, and thus inflict heavy losses upon the Arabs. The Israeli operations were characterized by:

- Operations in reinforced strike and demonstrative groups, consisting of aircraft flown by hand-picked highly experienced pilots;

- Extensive use of deception manoeuvring;

- Operations in demonstration groups, flyng at different places, different courses, and against different targets than the main strike group, that usually waited below the radar horizon or behind terrain obstacles that disturbed the radar picture, with the task of luring the opponent in the front of the stike group;

- Gradual introduction of several types of improved air-to-air missiles, starting with AIM-9D Sidewinder (the liquid-cooled version developed by the USN), and then Shafrir Mk.2, which caused an increase in engagement ranges, but also – due to limited front-aspect capability of these two weapons, and their good engagement envelope from the rear aspect – further shortened the duration of engagements;

- The deployment of the AIM-7E and then AIM-7E-2 “all-aspect” semi-active-radar-homing, medium range air-to-air missiles on IDF/AF F-4 Phantoms had a very small impact on the overall flow of air-to-air battles: these were especially not used at ranges “beyond the visual range” (BVR). In fact, the effective range from which they could have been used at the time was on the brink of the visual range – i.e. 10-12km – and well-known for their unreliability, so that the pilots tended to use them from shorter ranges, and then mainly to break cohesion of Arab formations and put Arab pilots on defensive early during the engagement. But, in general, Israeli Phantom-pilots were doing their best to avoid engagements with small (i.e. problematic to sight) and more nimble MiGs, while they considered the Sparrow a very poor weapon as well. Eventually, there was only a single engagement fought over “BVR” distance during this conflict, and that was set-up especially on US pressure.

Due to these facts alone, the Israelis tended to have the advantage of being in the offensive during most of the air-to-air engagements. Strategically, however, they were not interested in a wider conflict, and consequently it can be said that the Egyptians had the advantage of being in the offensive for most of 1968 and 1969. Clearly, the Israeli extensive testing of MiG-17s and MiG-21s helped them obtain intimate knowledge about the weaknesses of their opposition’s armament, and their best pilots developed highly effective tactics for flying Mirage IIICJ in dogfights against - theoretically - more nimble MiGs. This tactics was mainly dependent on the fact that original R-3S missiles as supplied to the Arabs used were not only technically unreliable, but also had a very narrow engagement envelope and a poor tracking capability, as well as that the Arab MiG-21-pilots were not very skilled in flying their aircraft at critically low speeds. The MiG-21PFs and MiG-21PFMs that were the mainstay of the EAF at the time also lacked the guns. Given that the minimal engagement range of the R-3S was 800m, and that it was essentially useless at levels bellow 500m, while most of the engagements of the Attrition War were fought at low levels and ranges around 400-700 meters, the MiGs were actually unarmed. Their pilots therefore had to look for executing slash attacks from the rear hemisphere against non-manoeuvring Israeli fighters, and learn doing so from ranges between 800 and 1.500m.

The Israelis, on the other side, would in air combat use the large delta-wings of their Mirages as air breakes to execute very tight turns and point their aircraft at the opponent, followed by the use of the afterburner to accelerate back into the fight. Such turns were excellent measure against R-3S, but would usually also enable the Mirage to position behind the MiG. Besides, the theoretically dangerous use of the afterburner was not that much of a problem in a situation where enemy infra-red homing missiles were usually useless. The situation could thus only change by the widespread use of the guns on MiGs, and due to more reliable and effective missiles – but also by much training of Arab pilots, which were not only flying more by their own instincts than according to any official tactical methods but also regularly firing their missiles too early (before all the firing parameters were established). It is pretty certain that the poor sighting over the long nose of the MiG-21 was one of decisive points for the later factor. Certainly, in a conflict against pilots that were so expertly trained in aerial gunnery – like Israelis were – the EAF had to suffer extensive losses before learning the lesson, and before being equipped with better-armed aircraft.

The air-to-air weaponry used during the War of Attrition was initially relatively simple: guns (which most of Arab MiG-21s were lacking) were used - usually with deadly results - from distances of 50 to 100 meters; air-to-air missiles at distances from 700 to 3.000 meters. The surviving MiG-21F-13s in EAF and SyAAF were armed with the NR-30, 30mm cannon, which was a powerful weapon, and were bellowed by pilots for this fact, as well as their agility. The MiG-21PF, MiG-21PFMs and similar sub-variants carried no such weapon and it would take some time until at least some were equipped with the gun-pod containing a two-barrel GSh-23 cannon, calibre 23mm. From the spring of 1970 also the much improved MiG-21MF was delivered to Egypt. This was not only equally fast like Phantom and Mirage at low levels, but also armed with built-in GSh-23 gun, and had also an additional hardpoint per each wing, enabling the theoretical capability to carry four air-to-air missiles. At the time the R-3S was the main armament of the aircraft, this was an important improvement, then it was often enough the case that both R-3S used by pilots of MiG-21PF/PFMs either malfunctioned or were fired out of the envelope: a MiG-21MF-pilot could not attempt a second attack with remaining two missiles, or fire all four in quick succession, thus increasing the probability of a hit. Nevertheless, this capability was not very often used, except by aircraft assigned for point defence: namely, during the Attrition War combat endurance was less important than the range, then especially the Egyptian MiGs were all too often confronted by Israeli fighter-bombers that were underway at a very high speed, and attempting their best to avoid interception. Consequently, the speed and the range were more important than the number of reasons, and for this reason the additional underwing pylons were more frequently used for carriage of additional fuel tanks.

The Israeli problems with early air-to-air missiles were already described to some degree above. From 1969, however, they started getting AIM-9D Sidewinders from the USA. These missiles were a considerable improvement compared to either the earlier AIM-9B (which Israel has never got), or its Soviet-copy,, the R-3S, then they were equipped with cooled seeker heads, with expanded envelope and tracking capability. Almost simultaneously with first deliveries of the AIM-9D the Israelis had finally brought also the Shafrir Mk.2 to a standard that permitted its deployment. The availability of the AIM-9D almost killed the Shafrir project, but eventually the decision was brought to start the production of the second version and – although this was not to prove as sophisticated in specific aspects as the US-weapon – the Shafrir was to prove more reliable and eventually score not only more kills during the Attrition War, but also become improved into the ultimate air-to-air weapon of the subsequent Yom Kippour/Teshreen War, in 1973.

With the arrival of the first F-4E Phantoms, in September 1969, the IDF/AF was also equipped with the AIM-7E Sparrow, a semi-active radar-homing weapon. Although the Sparrow was offering the advantage of a considerably expanded range (theoretically, it could be fired from distances as far as 15-20km from the targets), their pilots were not especially enthusiastic about it, finding this weapon complicated to use in manoeuvring battles and at low levels, and insufficiently reliable. Eventually, only very few kills were to be scored during the whole Attrition War, at least two of which were staged after heavy US-pressure. Sparrow eventually became the weapon of choice for Israeli Phantom-pilots that were underway on attack missions, then two could always be carried in the rear bays on the underside of the aircraft, not interfering with the carriage of bombs, ECM-pods, or external fuel tanks: consequently, even if the F-4 was carrying a maximal bomb-load, it could always take also two Sparrows for self-defence. Disappointed, however, the Israelis were to overcome even this problem, however, then they subsequently developed indigenous pylons for Sidewinder that could be mounted into Sparrow-bays of their Phantoms! These were to enter service by 1973 at least.

In the Begin...

The War of Attrition actually began only days after the end of the Six Day War: on 1 July 1967 Egyptian commandos attacked an Israeli armoured formation near Ras al-Ushsh. Even if already active, the UARAF was not yet fully ready to hit back: most of Egyptian airfields were repaired sufficiently to permit normal operations already before the ceasefire on 10 June, but the UARAF still needed some time to get new aircraft, reorganize battered units, and put together all the available pilots and personnel.

Through late June and early July 1967 the USSR was swift to supply a large number of new MiG-21s, Su-7s, and MiG-17s to Egypt: actually, the Egyptians preferred MiG-21s and MiG-17s to anything else, while also asking Soviets for more powerful aircraft that could increase their offensive capability. Moscow refused to deliver anything similar (like Yak-25s), instead preferring to develop and train the EAF in a purely defensive air arm, capable only of defending the air space over the Nile Delta, but was supplying Su-7s as well – to offer some kind of high-speed offensive capability. This lead to a sort of contradiction, as Egyptians tried to use their air power in a manner similar to that of the Israelis, while lacking the technology, firepower, and experience. Under such circumstances, the EAF was clearly on the best way to suffer extensive losses.

On 4 July 1967, the EAF flew the first offensive operation of this period, striking several targets in Sinai, but losing one MiG-17 in the process. A MiG-21 equipped for reconnaissance was sent over Israeli positions near el-Qantara on 8 July, but also shot down by air defences. Nevertheless, Cairo remained stubborn and the EAF was ordered to dispatch two Su-7s equipped with recce cameras into a new mission on the next morning. The Sukhois did several turns over the Sinai without facing any opposition, and in the afternoon the mission was repeated by two other Su-7s. This time, however, the Israelis waited for them, and one fighter was shot down by Mirages.

The EAF reacted by placing all its flying units on alert, and then starting a series of strikes against different Israeli positions. The situation culminated between the 11 and 15 July, when the IDF/AF deployed two squadrons of Mirage IIICJs to stop Egyptian attacks. In numerous air combats, the Israelis downed a total of two Su-7s, one MiG-17, and several MiG-21s. The Egyptians claimed to have shot down up to 15 enemies, but in fact their MiG-21s downed one Mirage the pilot of which ejected safely.

Subsequently, the Soviets forced the Egyptians to stand down, and continue the reorganization of their armed forces. But, in mid-October 1967, the EAF was back in the air and on offensive again, and new strikes were flown. The IDF/AF used the short break to develop two forward bases - at Bir Jifjafa, now called Refidim, and Ras Nisrani, now called Ophir. Each airfield had at lest four Mirages and sometimes also other aircraft on temporary deployment, with their crews on constant alert in order to be able to react to any Egyptian attack. In their first operation out of Refidim, on 12 October, for example, Israeli Mirages downed four Egyptian MiG-19s. On 21 October 1967, however, it was the Egyptian Navy which hit back, when its fast missile crafts sunk the Israeli destroyer Eilat with three SS-N-2 Styx surface-to-surface missiles. This was a turning point in the development of the naval warfare, then for the first time anti-ship missiles have proven their worth and capability of disabling major warships. Until that time this was only a theory, and although some smaller navies were already well-armed with fast missile crafts now all the larger navies around the world started to arm their major ships with anti-ship missiles as well.

Through 1969 and 1970 modified versions of the Nile Valley camouflage pattern were developed, including this one. Due to the heavy wear on aircraft it is not sure if the main colour in this case was indeed Olive Green: possibly, it was also Black, but it faded over the time. Note the gun-pod for the GSh-23 cannon carried under the centreline: the Egyptians learned their lesson of lacking gun armament on the MiG-21PF and MiG-21PFM and were swift to obtain a number of these pods. It remains unclear, however, if any were used during the Attrition War.

The Siege of Israel

By late 1967 and early 1968 the situation on the Suez quietened down, but now the Palestinian fighters became active with a series of attacks against Israeli troops, staged out of Jordan. Because of this, on 21 March 1968, the IDF initiated the operation „Inferno“ - a joint-forces strike against Palestinian bases around the city of Karameh, inside Jordan. The operation was initiated by helicopters deploying paras around the city, and then an armoured force attacking the bases. But, disturbed by the bad weather, the helicopters were late, and in the following battle the coordination of the Israeli forces broke down, causing heavy losses to the IDF.

On 8 September 1968, the Egyptian Army opened artillery fire against all Israeli positions along the Suez, killing ten Israelis and injuring 18. The Israelis attempted to respond, bombarding Suez and Ismailia. Two days later, EAF MiG-17s hit two Israeli posts in Sinai, losing one plane to Mirages, and on 31 October another Egyptian artillery strike killed 14 Israelis. This time, the IDF reacted with a commando attack, and in the following night the helicopters of the 123rd Sqn were used to deploy commandos at two Egyptian dams on Nile, the transformator station at Naj Hammadja, and the Qeena Bridge. All four targets were heavily damaged, and the operation caused a shock in Egypt, as it was clear now, that the Israelis can strike all around the country. The EAF responded by another MiG-17-strike, on 3 November, and this time Israeli interceptors were less successful, as during the ensuing combats with escorting MiG-21s no Egyptians were shot down, but one Mirage damaged.

After replacing the old S-58 helicopters of the 124th Sqn. by newer Bell 205s, on 1 December 1968 the IDF/AF launched another commando operation, „Iron“, against four bridges near Amman. This was a highly successful enterprise, in which all targets were destroyed without causing any losses to Jordanian or Palestinian civilian population. Two days later it was turn on PLO-bases in Jordan to be attacked, and while the strike flown by four SMB.2s was successful, one of the Israeli fighters was subsequently damaged during a brief air combat with RJAF Hunters.

After two new air combats – including one with Egyptians, on 12 December, in which a MiG-17 was shot down; and one with Syrians, on 24 December, in which two MiG-21s were destroyed – the next Israeli heliborne commando raid was undertaken on 28 December against the Beirut International Airport (IAP), by a force flown in Super Frelons and Bell 205s and in attempt to punish Lebanon for tolerating concentrations of Palestinian fighters on its soil. Within minutes, the Israelis blocked the roads to the airfield, and then destroyed 13 airliners of the Lebanese Middle East Airline before pulling out without any losses. The attack on Beirut IAP was a considerable shock for the Arabs, then it was not only executed in quite a nonchalant manner (the IDF commander of the raiding party walked into a restaurant of the main building and ordered a coffee), but also once again proved how far were the Israelis ready to go in retaliation for Arab terrorist attacks. It was, however, not to have any deterrent effects.

Meanwhile, by the late 1968, the EAF was completely reorganized into two separate arms. The EAF was now to control foremost the strike assets, like Su-7s, MiG-17s, and MiG-21s, while the air defence of the Egyptian air space was taken over by the EAF/Air Defence Command, which controlled two brigades of manned interceptors (MiG-21s) and several units equipped with SAMs and radars. The EAF/ADC was now to ease the burden of the EAF, and concentrate on fighting for air superiority over the Suez Channel, along which meanwhile no less but 150.000 Egyptian soldiers were deployed, while the EAF (now counting something like 50 MiG-21s, 80 MiG-19s, 120 MiG-17, 40 Su-7s, 40 Il-28s and a dozen or so Tu-16s) was to hit the Israelis on the Sinai. The Syrian Air Force was also back on the line, boasting a total of around 60 MiG-21s, 70 MiG-17s and 20 Su-7s by January 1969. In both air forces, newer MiG-21PFs have partially replaced the older MiG-21F-13s in interceptor units, and Su-7BMKs have taken the role of primary strikers from MiG-17s. Nevertheless, the Egyptians have upgraded their MiG-17s by adding new hardpoints and making them capable of carrying more weapons. While still heavily dependant of the Soviet help and instructions, both the EAF and the SyAAF have re-started their cooperation, as well as cooperation with numerous other air forces, foremost the Iraqi, Pakistani, Indian, Saudi and some others.

The Israelis, on their side, have meanwhile built a series of fortifications along the Suez, which became known as the „Bar-Lev Line“. This Line was actually established foremost to make any Egyptian attempt to swiftly cross the Canal and break deeper into Sinai before the Israeli Army could be mobilized, but not to completely prevent or stop any such efforts. However, with the time, misreporting about the Bar-Lev Line lead to the Israeli public developing a feeling about these fortifications being similar to those established in the well-known French “Maginot” Line. In connection with exaggerated claims about the superiority of the IDF in comparison of the Arab militaries, the Israeli public believed the “Bar-Lev Line” to be “impenetrable”: this was later to have severe repercussions for the government in Jerusalem during and after the war in 1973.

During February 1969, the IDF/AF bombed several targets inside Syria, and when Syrian interceptors reacted new air combats developed in which two MiG-17s and two MiG-21s were shot down. Actually, at the time the Israeli Air Force was still in a pretty bad shape, as the acquisition of new aircraft was initially slow. But, with US help, this was now rapidly to change. As first, Washington finally started to deliver 48 A-4E Skyhawks, and then also agreed to deliver 44 F-4E Phantoms. Very soon and again with the US help, the cooperation with France was re-established in a clandestine operation, which saw delivery of 50 „embargoed“ Mirage 5Js in crates to Israel with the help of US C-5 Galaxy transports. These aircraft were not the same 50 Mirage 5J built for Israel: these were taken by the French Air Force. Instead, between 1969 and 1971 Dassault has built a new series: the aircraft were paid for by the USA and then shipped to IAI, which put them together between late 1969 and 1973, explaining in the public that it was beginning production of an “indigenous” Israeli fighter, originally called Mirage Mod, but later Nesher. Officially, this was “possible” due to cooperation of a Swiss engineer who should have „revealed“ the secrets of Mirage 5 to Israel (and was even sentenced to several years of prison for doing this!). However, the company for which he was working was involved only in the production of Atar engines, and he could in no way have supplied the entire technical documentation need for the Israelis to build a completely new fighter.

Actually, the whole operation had to be organized in such manner because French were now officially „Arab-friends“, and - after the coup against the Emperor Idriz of Libya, which brought Col. Qaddafi to power - supplying Mirage III and 5 fighters also to Libya (where these were actually flown by Egyptian pilots)! The clandestine US-French-Israeli connection was finally so far developed, that it lead to a project in which Mirage 5 was to be mated with a US-supplied J-79 engines by the IAI, in a project lead by US designer - Gene Salvay. Thus the „Kfir“ came into being, which, however, entered production only after the war in 1973. Nevertheless, in the meantime the IAI was able to – again with considerable US support – re-engine its fleet of surviving Super Mystére B.2s with the J52 engine from the A-4 Skyhawk. This necessitated a longer fuselage, but offered a considerable advantage, then the aircraft could now carry a heavier payload as well. Consequently, they were equipped with additional hardpoints too.

From 1968 the IDF/AF received the first batch of 48 A-4E Skyhawks. These light fighters could nevertheless carry large amounts of weapons and were to prove their worth beyond any doubt, eventually leading to IDF/AF ordering additional examples of the A-4N, a version specifically developed according to the needs of the IDF/AF. (artwork by Mario Golenko)

The Wild West

Copyright 2002-3 by ACIG.org

د. يحي الشاعر[/b][/b]

عدل سابقا من قبل د. يحي الشاعر في الجمعة أكتوبر 09, 2020 7:16 pm عدل 1 مرات